Composition

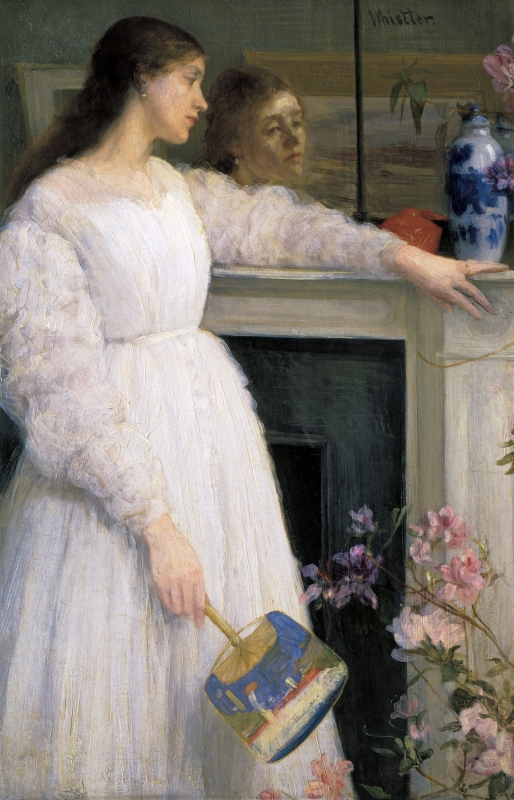

The composition has been related to Whistler's interest in Jean Dominique Ingres (1780-1867). Andrew McLaren Young (1913-1975) cited Ingres's portrait of the Comtesse d'Haussonville of 1845 (Frick Collection) as an interesting comparison with Whistler's 'reflective' portrait. 1

J. E. Millais, Before the Mirror, 1861, from Laver, James, A History of British and American Etching, 1929

A more immediate source may possibly be an etching attributed to John Everett Millais (1829-1896), Before the Mirror of 1861. 2

Another likely influence is The Bunch of Blue Ribbons (private collection) by Edward John Poynter (1836-1919), who had known Whistler as a student in Paris. 3 This was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1862 (cat. no. 144) and was owned by their mutual friend, Alexander Ionides (1840-1898). It was undoubtedly known to Whistler and could well have inspired him to produce a similar but more aesthetically harmonious composition.

An unsigned caricature that appeared in Punch on 21 February 1863, of a woman leaning with her left arm on a mantelpiece while gazing into a mirror, also displays a comparable attitude, combined with a mocking commentary on the fashionable crinoline (the like of which Whistler's model was not wearing). 4

Technique

The Pennells commented on Whistler's changing technique during the early 1860s, 'The paint is thinner on the canvas, the brush flows more freely. Method and design alike give the repose of the perfect work.' 5

Professor Joyce H. Townsend, Tate Britain, has provided a detailed analysis of the painting:

'The X-radiograph renders the lead white pigments used to paint the white dress and the flesh paint as light areas in the image. It can be seen in the X-radiograph, and in raking light from the top of the painting, that Whistler modified the position of the arms by incompletely scraping down the earlier position of the left one, with only the left elbow on the mantelpiece and that hand across the body. The right hand held something against the skirt: either an earlier fan, probably of the same size and shape, but with a different image upon it, hung from the right wrist by a loop of ribbon, or a bag or pouch of similar shape. Because so much paint was used for the dress, while only light areas of this object are depicted in the X-radiograph, all that can be said about its appearance is that there was a vague ‘X’ shape in darker paint running across it. The fan seen today is also rendered quite dark in the X-radiograph, which suggests that Whistler either added more white paint to the dress after he had made this change and begun to depict the fan with the Hiroshige image seen today, or else painted it onto an area that had been reserved for the purpose. Since the fan was painted at a late stage, its underlying paint having had time to dry, this could suggest that Whistler’s retouches in 1900 were to the dress. There is no evidence that the style of the dress changed at all during this development of the composition, so this might have been to repair surface damage.

The X-radiograph and the transmitted infrared image (this last emphasises black and dark brown pigments over white ones, rendering the darks colours as light areas in the image) indicate that the position of the head was adjusted, possibly more than once, It is more upright now, more in profile, and some 2 centimetres further to the left, making it ‘work’ less well with the angle of the reflected head in the mirror, which had fewer adjustments.

When the head was more tilted, the line of the skirt covered more of the grate. It is now less full.

None of these imaging techniques are likely to yield information on modifications to the vase or bowl, the reflected pictures on the opposite wall, nor the spray of flowers, but surface examination gives more clues. From the evidence of early photographs and commentaries, the adjustment to the arms, fan and head all occurred during painting, with no major modification since its first varnishing, before May 1864, and display later in that year. The effaced date of ‘1864’ was not rendered in any of these images, and the black and white ultraviolet light image (not reproduced here) did not yield any new information on its exact placement.

The transmitted infrared image offers a suggestion of ‘more’ hair when the head was tilted downwards, indicating that the hair was always loose and flowing. It also suggests that the fireplace was positioned first, the woman’s final posture established, the dress developed, the vase and bowl added, all before the fan and the flounces and sleeve puffs were added. There is no evidence that the sitter was ever depicted other than clothed: indeed, some of the pale flesh of the right arm, visible through the transparent white fabric, was created by applying pale pink paint over white for the fabric. Much of the sleeves were painted with a half-inch (12 mm) brush. The flowers in their final form were applied while the paint of the dress was still wet, but the present fan was done last, applied to dried paint. The paint was thickly applied everywhere, and the noticeable cracks in the fireplace near the original fuller skirt suggest less scraping-down than elsewhere. But some of the cracking may be due to several applications and removals of paint for the flowers.

Whistler’s retouchings of 1900 are not possible to identify from examination today. There are retouchings documented for a 1954 treatment, obvious at the left edge in ultraviolet light. Since the painting was first cleaned in 1892 and was re-varnished on that occasion, Whistler would have applied his retouchings on top of a varnish. In 1967 the painting was faced with tissue, impregnated and lined, all with wax/resin, at Tate. It is not explicitly stated that the varnish was removed and replaced, a step that often followed lining, so what we see today is likely the now-yellowed natural resin type varnish of 1892, spots of the original varnish beneath, and a combination of Whistler’s and later retouchings at the left edge. This suggests that whatever he did was minor in extent, since ultraviolet light generally reveals such old alterations.

The size and format of the painting are unaltered, as evidenced by Whistler’s own paint flowing onto the tacking margins, though the stretcher is not original, but dates from the 1967 treatment, when the first one would have been discarded. The medium/coarse canvas, with about 14 threads per centimetre, bears a colourman’s stamp ‘PREPARED BY / WINSOR & NEWTON / 38 RATHBONE PLACE / LONDON’ and a handwritten date ‘12.-63 / 2’. There is some dirt on the priming, beneath the paint – London air was full of pollution and particulate dust at this time. Keeping canvases clean before painting would not have been easy.

The preprimed canvas has a typical plain weave and a typical white priming applied in two layers, both containing lead white, chalk and oil. There is no coloured imprimatura of the type Whistler would use in many later portraits. However, an entry of 1967 in the Tate Conservation records (by the restorer who first lined the painting) suggests the composition was developed first in a caput mortuum colour (a pinkish purple, the terms denoting a purplish tone of red ochre). This might apply only to the figure. Later in the decade, Whistler would use a similar tone, lightened with lead white, for an imprimatura covering the whole canvas. Whistler used lead white-based paint exclusively for this canvas. It was a typical choice for the period. He used synthetic ultramarine and ultramarine ash to depict the vase on the mantelpiece, and rose madder and umber for the pink flowers. They, like the dress, include traces of Mars yellow, red ochre, Prussian blue and the other pigments noted, and their green leaves were mixed from synthetic ultramarine and cadmium yellow. Synthetic ultramarine and the rather pale ultramarine ash were much cheaper than the genuine ultramarine that he often favoured in later life. The red of the vase is also likely to be an inexpensive material rather than artists’ quality vermilion. The greenish background wall colour includes emerald green. All of these pigments except the unidentified red one have good light stability, and there is no evidence for any loss of colour through fading. The varnishes present today are all of natural resin type, and all have yellowed with age. Thus the greenish background today appears more green-yellow than it originally did.' 6

Conservation History

It was cleaned and varnished by Stephen Richards (1844-1900), picture restorer, in 1892. Whistler told the owner:

'I cannot help writing to you to congratulate you upon my beautiful pictures! - Are they not really lovely? - Now that I see them again I am filled with wonder to think that I should have personally known in a sort of easy comfortable friendly way - any one absolutely possessing such exquisite works! And in what a perfect condition! - Now - for some of them were in an abominable state when they came to me - but I took great pains with them and they were cleaned under my own supervision - and varnished, and returned to the pure state in which they originally left my hands - Of course it is a rare chance that they should be cared for in this way by myself - and I take this occasion to beseech you always to keep them under glass - The climate and smoke of England make it absolutely imperative.' 7

Fortunately Gerald Potter's son, J. C. Potter, thought it 'immensely improved by the cleaning.' 8

However, several years later, in 1900, the painting apparently required treatment, and was 'beautifully repaired' by Claude Chapuis (1829-1908), picture restorer in Paris, and Whistler 'retouched the places - so that now it is all right again.' 9 It was probably at this time, according to the Pennells, that Whistler painted out the original date '1864' because he 'did not see the use of those great figures sprawling there.' 10

Frame

- 1864: Whistler frame with Japanese & Chinese decoration, raised outer edge with flat crosshatch composition; inner frieze of incised whorl pattern and six roundels containing stylized rosettes at the corners, left and right midpoints; astragal site edge with incised decoration; English, possibly Joseph Green; whereabouts unknown.

- After 1892: Grau-style frame, oil gilded on pine with glazing door, English; this remained on the work.

- 1919: modified, glazing doors cut into the frame by the Tate. [FD] 108.5 x 82.8 cm (42 ¾ x 32 5/8"), [MW] 16.8 cm (6 5/8").

The Pennells' reproduction shows the poem Before the Mirror: verses under a picture by Algernon Swinburne printed on gold leaf and gilded directly over the incised whorls on the lower half of the frame. 11 This shows that the text was not an original part of the frame design, but was added later, for exhibition in 1865. It is the only known Whistler frame to contain text. This was a practice commonly associated with the Pre-Raphaelites. Because of this connection, it is possible that Joseph Green who made several of Rossetti’s frames during the 1860s made this frame for Whistler.

In 1892 during the preparations for the Goupil Gallery exhibition Whistler told J. C. Potter that it should be framed by Frederick Henry Grau (1859-1892):

' "The little White Girl" also ought to have a new frame. The old one is quite too weak for the picture - but there was no time to alter that - Do order one from Mr Grau. 570. Fulham Road. His prices are very little - and the pictures represent so much in comparison to what they cost!' 12

There are two possible interpretations for Whistler’s use of the word ‘weak’ in describing the frame that surrounded the Little White Girl. The first meaning could imply that the frame was not strong enough, physically, to support or protect the painting, thus suggesting poor craftsmanship or damage to the frame. The second meaning of the word ‘weak’ could imply that the frame was not strong enough, aesthetically, to support the painting. If this is the case, it illustrates a shift in Whistler’s artistic vision; the older frame had lost its original beauty and ultimately required replacing. It is not clear whether the portrait was reframed after the exhibition.

The current Grau-style frame could have been made after the 1892 exhibition, possibly when it was bought by Studd in 1893, and was certainly on the picture by 1904, as shown in the photograph reproduced above.

Soon after the painting’s accession by the Tate Gallery in 1919, a removable glazing door was made to protect the work. This enabled the glazing and painting to be removed from the frame while it remained on the wall. The door is indicated by thumbscrew fixings at top left and right, stamped with Tate’s accession number. 13

Notes:

1: Young, Andrew McLaren, James .McNeill Whistler, Milan, 1963, pp. 5, 7.

2: Laver 1929 [more] , repr. See also Yearwood, Claire Elizabeth, The Looking-glass world: Mirrors in Pre-Raphaelite Painting, 1850-1915, Ph.D. University of York 2014, fig. 97-98; and Pyne 2010 [more] , fig. 3.5 repr.

3: Staley, Allen, The New Painting of the 1860s: Between the Pre-Raphaelites and the Aesthetic Movement, Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, 2011, repr. p. 199. The Maas Gallery, London, 2016 (cat. no. 15), website at http://www.maasgallery.co.uk.

4: Anon., 'Punch's Advice to Ladies', Punch, 21 February 1863, repr. p. 73, with the text, 'As the Ladies are so warmly attached to their Crinolines, Mr. Punch strongly recommends that, instead of discarding them, they should wear them outside their dresses to serve as a Fire-guard.' YMSM 1980 [more] (cat. no. 52).

5: Pennell 1908 [more] , vol. 1, p. 128.

6: Professor Joyce H. Townsend, Tate Britain, Report of examination, September 2017. See also MacDonald, Margaret F., Joanna Dunn, and Joyce H. Townsend, 'Painting Joanna Hiffernan', in Margaret F. MacDonald (ed.), The Woman in White: Joanna Hiffernan and James McNeill Whistler, New Haven and Washington, 2020, pp. 33-45.

7: Whistler to J. G. Potter, [26/30 March 1892], GUW #01488.

8: J. C. Potter to Whistler, 4 April 1892, GUW #05006.

9: Whistler to Studd, [3 May 1900], GUW #03163.

10: Pennell 1908 [more] , vol. 1, p. 127.

11: Pennell 1911 A [more] , repr. f.p. 124. A print of this photograph, inscribed to Swinburne, was sold at Sotheby's, London, 11 July 1996 (lot 236).

12: Whistler to J. C. Potter, [26/30 March 1892], GUW #01488.

13: The frame has been re-gilded but by 2016 was flaking and dirty. Dr Sarah L. Parkerson Day, Report on frames, 2017; see also Parkerson 2007 [more] .

Last updated: 7th June 2021 by Margaret